Right, but as you say (with G-K), you have to be ready to cut spending. I personally would rather approach things with my conservative WR% with the hope that I never have to cut the buying power amount.

Well, as they say, "hope is not a plan".

Something they taught us in one of the classes I took was "The person with the best Plan B is the one most likely to be the winner."

This is one of those interminable topics. We are trying to balance two conflicting things, to maximize the annual withdrawals, to not run out of money, to not have to reduce any annual withdrawal. The problem is we do not know what will happen in the future.

When the portfolio goes down, you don't know if this is just a momentary pothole, or if it is the start of a long downward slope.

If you want to never run out of money, you go with a constant percentage draw --- but the draws will fluctutate wildly. Somebody recently posted a spreadsheet showing a draw of $59K one year and a draw of $48K the next year, in the 2008/2009 period.

As G-K, Kitces, Burns, and others have said, *most* of the large market jumps are smoothed out over the next few years, so abruptly changing your draw is not neccessary. But changing it *will* be neccessary if the jump does not revert. That's the case no matter how you manage the changes--the ultimate reduction is if your account goes to zero, and you have $0 withdrawls forever.

These strategies have a Plan B for the case of portfolio losses: slowly reduce withdrawals.

The "take 3%, period" strategy has no Plan B. The real world imposes its own Plan B -- "...and then you die."

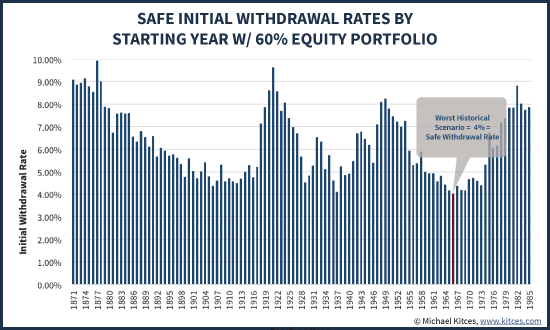

The alternative to possibly making periodic reductions is to take a low SWR. But that is essentially taking a permanent preventative reduction.

Take 3% with no reductions, or take 5% with the possibility of having to reduce to 4% or 3%. Or a low probability of 2%. It sounds to me like a boxer taking a dive to avoid getting punched. Preemptively declaring defeat, and starting off with the initial presumption that you will lose anyway.

If you are okay with 3%, then why not take 5% and then reduce down to 3% if and when it ever becomes neccessary? Because looking at past history, there is less that a 1-in-20 chance that it will be neccessary. But if those odds catch up with you -- well, you have a plan that will let you survive.

We all know that when push comes to shove we *will* reduce our spending in adverse curcumstances. So why not make that an explicit part of the plan? Whether you are taking 5% or 3%, if the market crashes 50% you'll hunker down and avoid all unneccessary spending. So a plan that has you cutting your draw is just explicitly stating what you'll do.