Htown Harry

Thinks s/he gets paid by the post

- Joined

- May 13, 2007

- Messages

- 1,525

Here's an interesting article in the May Journal of Financial Planning:

Sustainable Withdrawal Rates from Retirement Portfolios: The Historical Evidence on Buffer Zone Strategies

Two links to the article (the first requires scrolling through the magazine to page 46 and may require a log-in):

Digital Edition

Sustainable Withdrawal Rates from Retirement Portfolios: The Historical Evidence on Buffer Zone Strategies by Walter Woerheide, David Nanigian :: SSRN

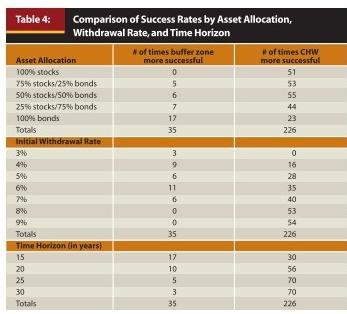

In a nutshell, they applied the methodology of Cooley, Hubbard, and Walz (CHW) from their 2011 Trinity study update, then ran the numbers with a cash buffer to avoid withdrawals during a down market.

Am I missing something, or do these numbers go against the conventional wisdom here at ER.org? Obviously, the very high percentage withdrawals would be outliers here, but the lack of a significant advantage for using a buffer at a 4% withdrawal rate certainly caught my eye.

They did make a good point at the very end. Investor psychology being what it is, a buffer can be a good thing if it's what a person needs to be comfortable with the higher stock percentages that increase portfolio survival rates over the long term.

Sustainable Withdrawal Rates from Retirement Portfolios: The Historical Evidence on Buffer Zone Strategies

Two links to the article (the first requires scrolling through the magazine to page 46 and may require a log-in):

Digital Edition

Sustainable Withdrawal Rates from Retirement Portfolios: The Historical Evidence on Buffer Zone Strategies by Walter Woerheide, David Nanigian :: SSRN

In a nutshell, they applied the methodology of Cooley, Hubbard, and Walz (CHW) from their 2011 Trinity study update, then ran the numbers with a cash buffer to avoid withdrawals during a down market.

The results surprised me a little bit, showing that the benefits of not selling in a down market are very frequently outweighed by low returns on the cash portion of the portfolio. Except at a low 3% withdrawal rate or possibly with a 100% bond portfolio, a cash buffer method was found to be less successful than just riding the market and keeping the withdrawals consistent year-by-year.Few of these types of studies consider the role of cash in decumulation portfolios. We are aware that some financial planners advocate the use of buffer zones as a component of a decumulation portfolio. See, for example, Evensky and Katz (2006) and Horan (2011) for a discussion of this strategy.

A buffer zone involves the use of money market funds to assure the safety of withdrawals that will be taken over the near future and to avoid selling in an undervalued market. For example, suppose there is no inflation (for simplicity) and a person has a $100,000 portfolio, and he or she wants to withdraw 5 percent of this amount, i.e., $5,000, per year. If this person were using, say, a three-year buffer zone, then he or she would put three years’ worth of withdrawals, i.e., $15,000, into cash. The rest, $85,000, goes into an investment portfolio that consists of risky assets.

At the end of the year, this person withdraws $5,000 from the investment portfolio if the investment portfolio goes up during the year. If the investment portfolio goes down in value, then the retiree takes the money from the cash holdings. If the investment portfolio goes up the second year after going down the first year, then the retiree takes the annual withdrawal from the investment portfolio, and also liquidates enough of the investment portfolio to bring the cash position back up to its original value. The retiree takes direct withdrawals from the investment portfolio without replenishing the cash position only if the investment portfolio has gone down four or more years in a row.

The basic question in this paper is: would the use of buffer zones have enhanced or reduced the portfolio success rates over what would have been achieved by not using buffer zones over our test period. We will examine four strategies involving the use of buffer zones and a variety of withdrawal rates. We then compare the success of each strategy to the success of the traditional withdrawal strategy as described in CHW (2011).

Am I missing something, or do these numbers go against the conventional wisdom here at ER.org? Obviously, the very high percentage withdrawals would be outliers here, but the lack of a significant advantage for using a buffer at a 4% withdrawal rate certainly caught my eye.

They did make a good point at the very end. Investor psychology being what it is, a buffer can be a good thing if it's what a person needs to be comfortable with the higher stock percentages that increase portfolio survival rates over the long term.