RonBoyd

Give me a museum and I'll fill it. (Picasso) Give me a forum ...

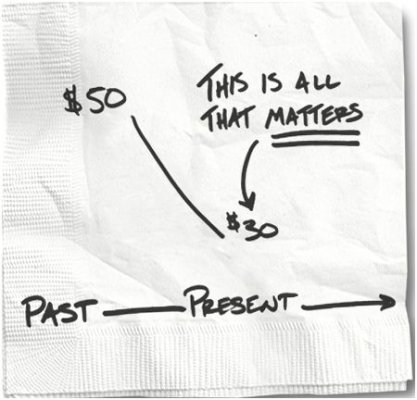

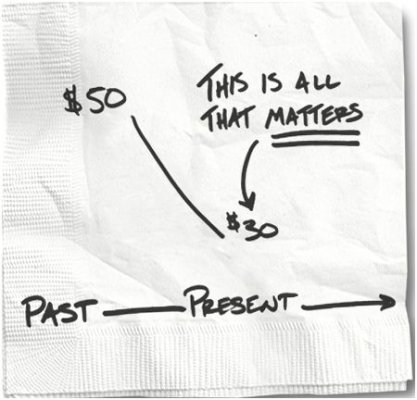

Carl Richards, a financial planner, has been explaining the basics of money through simple graphs and diagrams.

NYTimes: Your Money

For instance:

or

NYTimes: Your Money

For instance:

3. Your portfolio was worth $500,000 at the top of the tech bubble in early 2000, and you still think about that value each time you open your statement and see that it’s worth less than that. You just want to get back to your high-water mark of $500,000.

This may not have any impact on your decisions, but it sure is affecting your life. I know people like this, still holding on to a value in the past. It is like that guy next door who is still telling stories of his glory days in high school football.

The past is the past. All that matters now is making the correct decision for today.

or

Investor behavior matters a lot. In fact, it probably matters more than skill. To understand why this is true, first you need to understand one fundamental concept: Investment returns and investor returns are almost always different.

An investment return is what you get if you invest your money at the start of a period and then don’t touch it. You don’t buy or sell. You just buy and hold. But real people in the real world don’t invest that way.

Real people are always chasing performance and investing by looking in the rear-view mirror. The result of this never-ending hunt for the best investment causes us real trouble.