jkern

Full time employment: Posting here.

While driving the other day, I was casually listening to the Rick Edelman show on the radio. Similar to many financial shows, he promotes investing in stocks & bonds. Due to the recent market drop, he was quoting long term Average Annual Rates of Return to bolster his view. He quoted numbers from 1926 and other cherry picked start and stop dates.

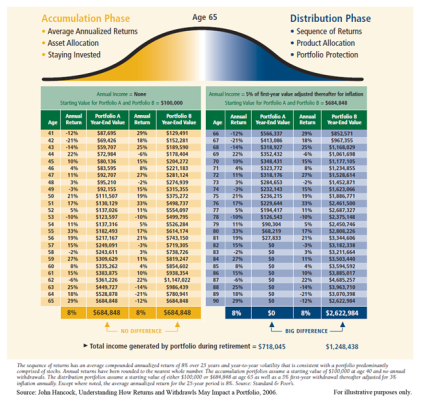

This got me thinking that the Rick Edelman's of the world rarely if ever mention sequence of return risk. Even when they do mention it, I believe they significantly understate its importance on the final outcome of your portfolio.

So, given the amount of free time I have, I calculated my own Ave Annual Rate of Return during my accumulation phase (1987 to June 2009). It equals approximately 2.5% with mostly a 80/20 stocks/bonds portfolio. It appears the sequence of returns is by far the largest factor on a portfolio during the accumulation phase and probably the withdrawal phase too.

Does anyone else feel the same way or am I missing something?

This got me thinking that the Rick Edelman's of the world rarely if ever mention sequence of return risk. Even when they do mention it, I believe they significantly understate its importance on the final outcome of your portfolio.

So, given the amount of free time I have, I calculated my own Ave Annual Rate of Return during my accumulation phase (1987 to June 2009). It equals approximately 2.5% with mostly a 80/20 stocks/bonds portfolio. It appears the sequence of returns is by far the largest factor on a portfolio during the accumulation phase and probably the withdrawal phase too.

Does anyone else feel the same way or am I missing something?