IndependentlyPoor

Thinks s/he gets paid by the post

I must admit that I hate the way the stock market grants moral absolution to all of us who profit from companies that do things the we would consider immoral, but I don't have any idea at all of what to do about it, other than what Ziggy said.

I also hate to spoil this interesting series of posts with another Geek bomb, but folks asked about consistent time periods and three fund portfolios, so I ran some.

I optimized three fund portfolios for maximum return/volatility. (Not the same as maximizing for minimum volatility.) Each portfolio consisted of one fund from Vanguard's general stock category, one from the international/aggressive/sector categories, and one bond fund.

Again, with 20/20 hindsight, the optimizer pretty much eliminated the general stock funds from the portfolios. It seems like barbell portfolios with sector funds and treasuries was where to be since 1991.

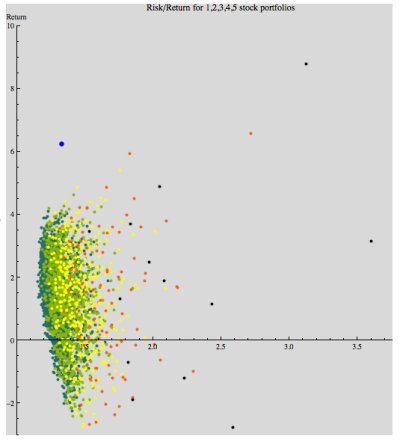

The chart also shows the risk/return of Vanguard's balanced funds for comparison, but I did not include the balanced funds in any portfolios. Likewise, the chart shows the risk/return of the individual funds that make up the portfolios.

Here is a screenshot of the interactive graphic.

When you hover the cursor over a point, it shows the fund name(s) and allocations for the portfolios. Here, the popup is showing Wellesley.

The three fund portfolios are in red (although the general stock fund allocation was optimized to zero in many),

the balanced funds in blue,

and the individual funds that make up the portfolios in purple.

One thing that jumps right out at you is that the individual funds have much more volatility than the portfolios, so something is working.

You Wellesley fans should be happy to see that it does well in this comparison.

You need the free Mathematica Player for the interactive graphic.

It is here:

Wolfram Mathematica Player: Download

And here is the link to the interactive graphic:

http://www.wolfram.com/solutions/in...441069&filename=Three+fund+portfolios+pub.nbp

I also hate to spoil this interesting series of posts with another Geek bomb, but folks asked about consistent time periods and three fund portfolios, so I ran some.

I optimized three fund portfolios for maximum return/volatility. (Not the same as maximizing for minimum volatility.) Each portfolio consisted of one fund from Vanguard's general stock category, one from the international/aggressive/sector categories, and one bond fund.

Again, with 20/20 hindsight, the optimizer pretty much eliminated the general stock funds from the portfolios. It seems like barbell portfolios with sector funds and treasuries was where to be since 1991.

The chart also shows the risk/return of Vanguard's balanced funds for comparison, but I did not include the balanced funds in any portfolios. Likewise, the chart shows the risk/return of the individual funds that make up the portfolios.

Here is a screenshot of the interactive graphic.

When you hover the cursor over a point, it shows the fund name(s) and allocations for the portfolios. Here, the popup is showing Wellesley.

The three fund portfolios are in red (although the general stock fund allocation was optimized to zero in many),

the balanced funds in blue,

and the individual funds that make up the portfolios in purple.

One thing that jumps right out at you is that the individual funds have much more volatility than the portfolios, so something is working.

You Wellesley fans should be happy to see that it does well in this comparison.

You need the free Mathematica Player for the interactive graphic.

It is here:

Wolfram Mathematica Player: Download

And here is the link to the interactive graphic:

http://www.wolfram.com/solutions/in...441069&filename=Three+fund+portfolios+pub.nbp