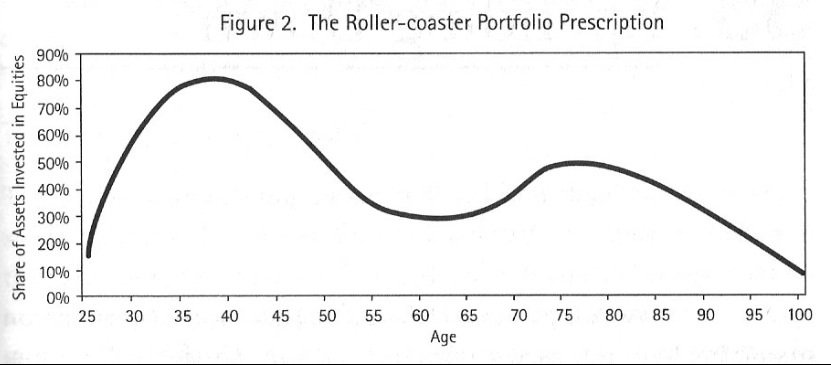

"The report finds that those who take the opposite approach—by reducing equity exposure right after retirement and then gradually raising it over time—are likely to make their money last longer."

Who'd have thought this?

"According to the research, those who start retirement with 20% to 30% in stocks and end up with 50% to 70% in stocks can withdraw 4% of their portfolio per year and give themselves annual raises to compensate for inflation over 30 years, even in the worst market scenarios. (The authors examined 10,000 simulations and assumed average annual returns of 6.5% for stocks and 2.4% for bonds.)

In contrast, those who keep 60% in stocks throughout retirement or who taper to a 30% equity allocation from 60% are likely to run out of money after 28 years in the 5% of worst-case scenarios"

A New Asset-Allocation Strategy for Investing in Retirement - WSJ.com

Who'd have thought this?

"According to the research, those who start retirement with 20% to 30% in stocks and end up with 50% to 70% in stocks can withdraw 4% of their portfolio per year and give themselves annual raises to compensate for inflation over 30 years, even in the worst market scenarios. (The authors examined 10,000 simulations and assumed average annual returns of 6.5% for stocks and 2.4% for bonds.)

In contrast, those who keep 60% in stocks throughout retirement or who taper to a 30% equity allocation from 60% are likely to run out of money after 28 years in the 5% of worst-case scenarios"

A New Asset-Allocation Strategy for Investing in Retirement - WSJ.com