Something that is generally not analyzed about Roth conversions is that the models are very unrealistic in that you have to use the same stock/bond allocation in all your accounts or the calculation mixes the higher returns of stocks with the benefits of Roth conversions and you learn nothing useful. However, no one is going to hold assets that way if they can help it, they want bonds in tax deferred to limit its growth and stocks in taxable and Roth.

The simple act of optimizing asset location looks like it drastically cuts the optimum amount of Roth conversions. In my own case, it cuts the optimum Roth conversion in half, from 70% of the initial tax deferred account if I used all accounts at equal asset allocations, to 35% when studied in more detail.

To walk through what happens, eventually, if you do enough Roth conversions and enough time passes, RMDs eat away at tax deferred and your tax deferred fills with bonds as your stocks grow and you rebalance to maintain your asset allocation. The overflow bonds have to go somewhere and for me Roth was less bad than taxable (yes I tested). But roughly speaking, once that overflow got serious, I wasn't getting additional much benefit from doing more conversions. This filling tax deferred with bonds happens in the No Roth case too, just slower.

The only consumer level tool I'm aware of that can tackle asset location optimization is Pralana Gold. It cost me ($99 1st year, I believe will be $49 renewal, needs Excel) and is very full featured (it's complex, but you don't write formulas and the layout, menu and manuals are good, but you really should be familiar with spreadsheets before tackling this). It reports the overall asset allocation and allows you to adjust the allocation of each type of account (taxable, tax deferred, Roth) up to four times during your lifetime. So I start with the overall stock allocation a couple percent below my target and over say six years, it grows to 2-3% above target, so I rebalance to a couple percent below target and repeat. This is manual and requires lots of fiddling between screens to get the amount above and below target to balance out each time to make the answer reasonably good.

Pralana Gold then gives both the NW and a rough estimate of the heir's taxes. If you are going to give your estate to charity, then NW at death is the right measure as the charity doesn't pay taxes on any bequests. I get only a very slight improvement in NW at death converting up to the 10% bracket and net losses after that.

If you are leaving your estate to heirs, then the heir's taxes are also part of the picture. I am using Roth conversions to help my heirs, so I include their taxes. Pralana Gold's estimate of heir's taxes is low in my case since conversion taxes came out of taxable and that leaves a smaller taxable account generating slightly lower taxes from dividends during the 10 year liquidation period for the heirs.

I'm sure your reaction is the incremental taxes during heir liquidation have to be very small - yes indeed, but the benefit for the Roth is pretty small too, so it is a noticeable part. (I had to do those estimates outside Pralana Gold). The results below include a present value calculation to bring the benefits back to current $, not after 40 years of compounding.

My final results show Roths net interesting, but not life changing money. (In my ready, fire, aim approach I've already converted past the optimum for this year)

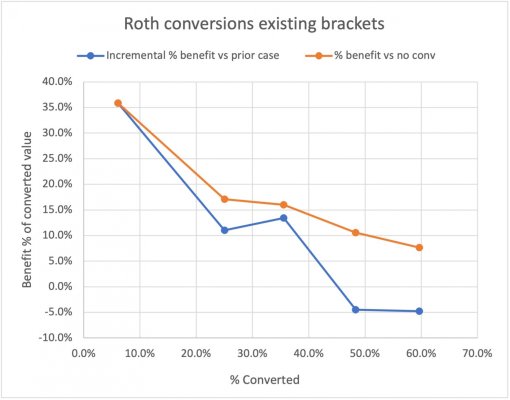

The charts below show the benefit for the Roth with optimized asset location, with the values after heir liquidation corrected to present values. Each point on the graph was the max I could convert and stay within a given IRMAA tier or tax bracket.

The orange line is the benefit as a fraction of the conversion. For example, the third orange point (optimum) is about a 16% benefit on a conversion of 35.5% of the account = 5.7% of the tax deferred account balance can be gained with optimum Roth strategy (if the world unfolds exactly as assumed). The blue line is the incremental benefit between points, which goes negative when converting at higher tax brackets or IRMAA tiers.

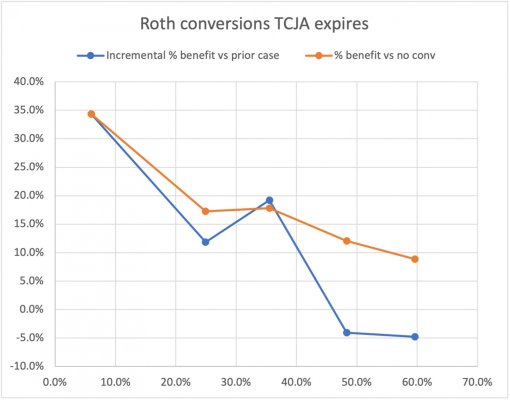

I also ran a case positing the expiration of the TCJA, figuring that would show the much higher conversions I expected. Nope. It didn't change the optimum conversion amount.

A few more details - MFJ, 61 & 60, assuming I die at 80 and DW lives to 92, no pension, SS at 70 for me and spousal at 67 for DW, assumed 5% real on stocks, 1% real on bonds, 80/20 AA. Mid seven figures, 50/50 taxable/tax deferred. Seems like Roths are more of an "excess return insurance" or "I die early" insurance.

Like everything around Roth conversions, the results are very individual, so what is true for me may be ridiculous for others.

The simple act of optimizing asset location looks like it drastically cuts the optimum amount of Roth conversions. In my own case, it cuts the optimum Roth conversion in half, from 70% of the initial tax deferred account if I used all accounts at equal asset allocations, to 35% when studied in more detail.

To walk through what happens, eventually, if you do enough Roth conversions and enough time passes, RMDs eat away at tax deferred and your tax deferred fills with bonds as your stocks grow and you rebalance to maintain your asset allocation. The overflow bonds have to go somewhere and for me Roth was less bad than taxable (yes I tested). But roughly speaking, once that overflow got serious, I wasn't getting additional much benefit from doing more conversions. This filling tax deferred with bonds happens in the No Roth case too, just slower.

The only consumer level tool I'm aware of that can tackle asset location optimization is Pralana Gold. It cost me ($99 1st year, I believe will be $49 renewal, needs Excel) and is very full featured (it's complex, but you don't write formulas and the layout, menu and manuals are good, but you really should be familiar with spreadsheets before tackling this). It reports the overall asset allocation and allows you to adjust the allocation of each type of account (taxable, tax deferred, Roth) up to four times during your lifetime. So I start with the overall stock allocation a couple percent below my target and over say six years, it grows to 2-3% above target, so I rebalance to a couple percent below target and repeat. This is manual and requires lots of fiddling between screens to get the amount above and below target to balance out each time to make the answer reasonably good.

Pralana Gold then gives both the NW and a rough estimate of the heir's taxes. If you are going to give your estate to charity, then NW at death is the right measure as the charity doesn't pay taxes on any bequests. I get only a very slight improvement in NW at death converting up to the 10% bracket and net losses after that.

If you are leaving your estate to heirs, then the heir's taxes are also part of the picture. I am using Roth conversions to help my heirs, so I include their taxes. Pralana Gold's estimate of heir's taxes is low in my case since conversion taxes came out of taxable and that leaves a smaller taxable account generating slightly lower taxes from dividends during the 10 year liquidation period for the heirs.

I'm sure your reaction is the incremental taxes during heir liquidation have to be very small - yes indeed, but the benefit for the Roth is pretty small too, so it is a noticeable part. (I had to do those estimates outside Pralana Gold). The results below include a present value calculation to bring the benefits back to current $, not after 40 years of compounding.

My final results show Roths net interesting, but not life changing money. (In my ready, fire, aim approach I've already converted past the optimum for this year)

The charts below show the benefit for the Roth with optimized asset location, with the values after heir liquidation corrected to present values. Each point on the graph was the max I could convert and stay within a given IRMAA tier or tax bracket.

The orange line is the benefit as a fraction of the conversion. For example, the third orange point (optimum) is about a 16% benefit on a conversion of 35.5% of the account = 5.7% of the tax deferred account balance can be gained with optimum Roth strategy (if the world unfolds exactly as assumed). The blue line is the incremental benefit between points, which goes negative when converting at higher tax brackets or IRMAA tiers.

I also ran a case positing the expiration of the TCJA, figuring that would show the much higher conversions I expected. Nope. It didn't change the optimum conversion amount.

A few more details - MFJ, 61 & 60, assuming I die at 80 and DW lives to 92, no pension, SS at 70 for me and spousal at 67 for DW, assumed 5% real on stocks, 1% real on bonds, 80/20 AA. Mid seven figures, 50/50 taxable/tax deferred. Seems like Roths are more of an "excess return insurance" or "I die early" insurance.

Like everything around Roth conversions, the results are very individual, so what is true for me may be ridiculous for others.