Midpack

Give me a museum and I'll fill it. (Picasso) Give me a forum ...

We often see posts encouraging Roth conversions to fill to the 12% bracket, and that seems a no brainer. If you convert to 12% and find yourself forced into the 22% bracket from 70 on, you may regret it. Is there more universal advice?

*** Knowing everyone has to assess all the other factors that go into the Roth conversion decision. ***

After the analysis I’ve been though, and though people have probably already said it (and I missed it) - I’m thinking a slightly better starting point might be:

Convert to the fill whatever bracket you’ll be in from age 70 on if you hadn’t done any conversions.

IOW if you do NO conversions and that will put you in the 22% (24%, 32%...) bracket from age 70 on due to Soc Sec, RMD, distributions, cap gains and other income, you’ll probably reduce taxes by converting up to the 22% (24%, 32%...) income bracket every year before age 70. If tax rates don’t change, your nest egg final amount will be about the same - you’ll pay less in federal taxes overall, but you’ll forego the returns on the money used to pay taxes on conversions. However, there are other worthwhile $ benefits to widows, heirs, etc. And if future tax rates take more (as I expect long term), you’ll save even more on federal taxes and increase your nest egg final amount some. State taxes you’ll have to consider separately.

*** Knowing everyone has to assess all the other factors that go into the Roth conversion decision. ***

After the analysis I’ve been though, and though people have probably already said it (and I missed it) - I’m thinking a slightly better starting point might be:

Convert to the fill whatever bracket you’ll be in from age 70 on if you hadn’t done any conversions.

IOW if you do NO conversions and that will put you in the 22% (24%, 32%...) bracket from age 70 on due to Soc Sec, RMD, distributions, cap gains and other income, you’ll probably reduce taxes by converting up to the 22% (24%, 32%...) income bracket every year before age 70. If tax rates don’t change, your nest egg final amount will be about the same - you’ll pay less in federal taxes overall, but you’ll forego the returns on the money used to pay taxes on conversions. However, there are other worthwhile $ benefits to widows, heirs, etc. And if future tax rates take more (as I expect long term), you’ll save even more on federal taxes and increase your nest egg final amount some. State taxes you’ll have to consider separately.

https://www.betterment.com/resources/common-roth-conversion-mistakes/2. Convert Too Much

Roth conversions can be a powerful strategy, but blindly converting can end up causing more harm than good.

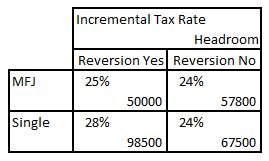

A common strategy used to avoid paying more in taxes than you may have to is called “bracket filling.” You determine how much room you have until you hit the next tax bracket, and then convert just enough to “fill up” your current bracket.

For example, if you are married filing jointly and have taxable income of $100,000, then you have about $68,400 of room before jumping from the 22% Federal tax bracket to the 24% bracket. It’s worth noting that certain state tax rates can be impacted as well and the rules vary state to state.

Converting any more than what you have left to fill up your current tax bracket would likely cause you unnecessary taxes. You can work with your tax preparer to find exactly how much room you have and how much to convert.

3. Convert Too Little

On the other end of the spectrum, many people are too conservative when calculating how much to convert and end up missing out on valuable room in their tax brackets.

To be clear, going into the next bracket is probably not what you want to do. However, nobody knows exactly what bonus they’ll get, or how many dividends they will receive, so guessing the exact dollar amount is impossible. Since we no longer have the luxury of undoing a Roth conversion, it’s more important than ever to take extra care when running the numbers.

Last edited: