Kevin Drum:

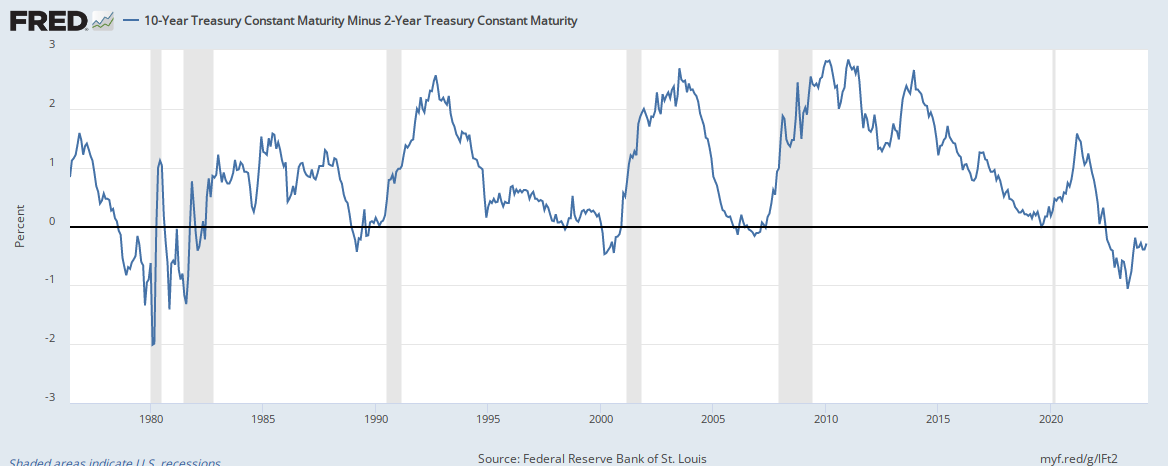

"Generally speaking, the yield on a 5-year treasury bond should be higher than it is on 3-year bond. After all, the longer term means you’re taking on a little more risk. Today, however, after years of breathless waiting, this is no longer true. The yield curve has “inverted,” and as I type this both 3- and 5-year bonds are yielding 2.84 percent.

"The conventional wisdom says that this is because investors are betting on the Fed reducing interest rates in the near future. With lower rates around the corner, investors want to lock in the higher rates currently available for as long as they can, so they’re snapping up 5-year treasurys, which in turn has reduced their yield below the 3-year rate.

"That all makes sense, but why do investors think the Fed will shortly be reducing interesting rates? Because a recession is coming.

"That’s the conventional wisdom, anyway. You may decide for yourself whether to believe it."

https://www.motherjones.com/kevin-drum/2018/12/the-yield-curve-has-inverted/

"Generally speaking, the yield on a 5-year treasury bond should be higher than it is on 3-year bond. After all, the longer term means you’re taking on a little more risk. Today, however, after years of breathless waiting, this is no longer true. The yield curve has “inverted,” and as I type this both 3- and 5-year bonds are yielding 2.84 percent.

"The conventional wisdom says that this is because investors are betting on the Fed reducing interest rates in the near future. With lower rates around the corner, investors want to lock in the higher rates currently available for as long as they can, so they’re snapping up 5-year treasurys, which in turn has reduced their yield below the 3-year rate.

"That all makes sense, but why do investors think the Fed will shortly be reducing interesting rates? Because a recession is coming.

"That’s the conventional wisdom, anyway. You may decide for yourself whether to believe it."

https://www.motherjones.com/kevin-drum/2018/12/the-yield-curve-has-inverted/