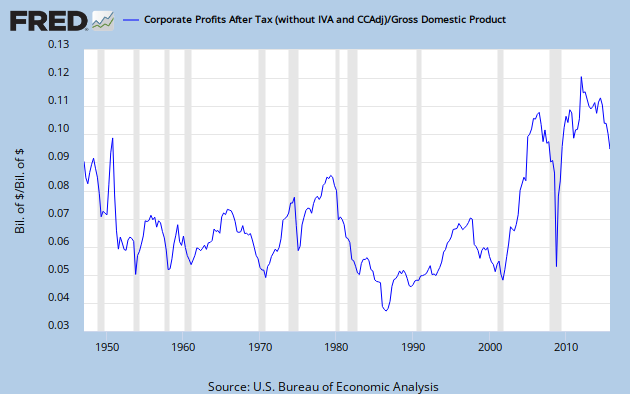

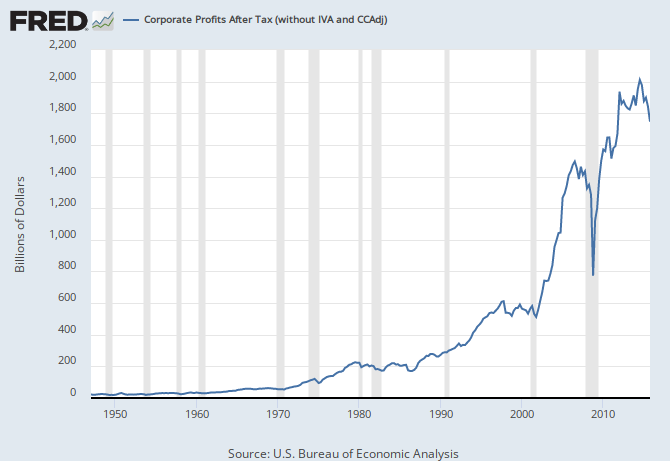

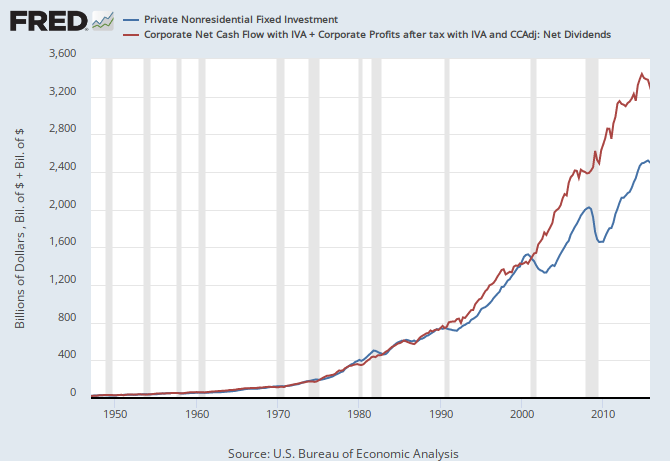

If monopoly power increased, one would expect to see higher profits, lower investment as firms restricted output, and lower interest rates as the demand for capital was reduced. This is exactly what we have seen in recent years!

Is the increased-monopoly-power theory plausible? The Economist

makes the best case I have seen for it, noting that (i) many industries have become more concentrated, (ii) we are coming off a major merger wave, (iii) there is some evidence of greater profit persistence among major companies, (iv) new business formation has declined, (v) overlapping ownership of companies that compete has become more common with the rise of institutional investors, and (vi) leading technology companies such as Google and Apple may be benefiting from increasing returns to scale and network effects.