I see them as similar in that the risk is living long and if you make choices to have the most money when you die don't you similarly minimize the likelihood of running out of money if you have adverse experience? I'm not certain that they are one and the same but they are certainly similar.

Sometimes they are the same, sometimes they aren't. A thought experiment: You are offered two options for your retirement savings:

1) Bet everything on one roll of a fair die. Pick any number, and you'll get paid 10:1 odds if you are right, lose your money if wrong.

2) Don't bet

Clearly, from a net expected value POV, the first option is best. Your chance of picking the right number is 1:6, but you are being paid 10:1, it's a no-brainer. This is clearly the best way to maximize the expected amount of money, even with the possibility of losing all of it.

Most of us would choose option 2. It doesn't produce the highest expected outcome, but still we would choose it. That's because our objective isn't to maximize our expected outcome, but to maximize chances of making our spending power last through our living years. Not betting (and continuing to invest our money as normal) does that better than Option 1.

There are variations of this, but the marginal utility of money decreases as we have more of it. So, for most f us, if our total retirement income was a rock-solid $3K per month (inflation-adjusted) forever, we wouldn't take a 50:50 bet where we could lose $1500 per month even if the gain would be $2000 per month. The "negatives" of trying to get by on $1500/mo are much higher than the "positives" of a new monthly spending of $5000/mo.

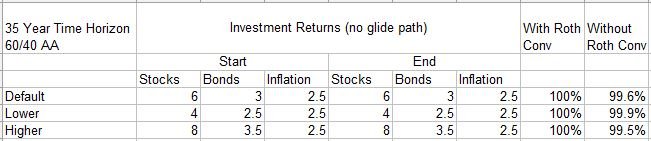

The decision to delay SS is an obvious place where this dynamic comes into play, but this Roth conversion question is another one. Trying to reduce taxes

if our portfolio "hits one out of the park" may not make sense if it comes at the risk of reducing available funds if our portfolio later does poorly and is barely keeping the heat on in the winter.