MasterBlaster

Thinks s/he gets paid by the post

- Joined

- Jun 23, 2005

- Messages

- 4,391

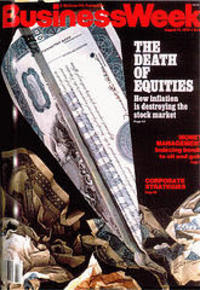

Rethinking Stocks for the Long Haul - BusinessWeek

the combination of recent experience and a substantial body of finance research makes a convincing case that there's no safety in owning stocks for 10, 15, 20, 30 years—quite the opposite. Far too many investors may be taking on more risk than they know with their retirement nest egg in target-date funds or comparable portfolios put together by a DIY generation of savers. The risk in stocks is that they may stay down for a long time, wiping out a generation of savers who could be long dead before the market starts climbing again.