Ed_The_Gypsy

Give me a museum and I'll fill it. (Picasso) Give me a forum ...

In re OP:

Pastafarian here.

Our basic needs and more are covered by SS, but we are drawings down our TIRA and my Roth.

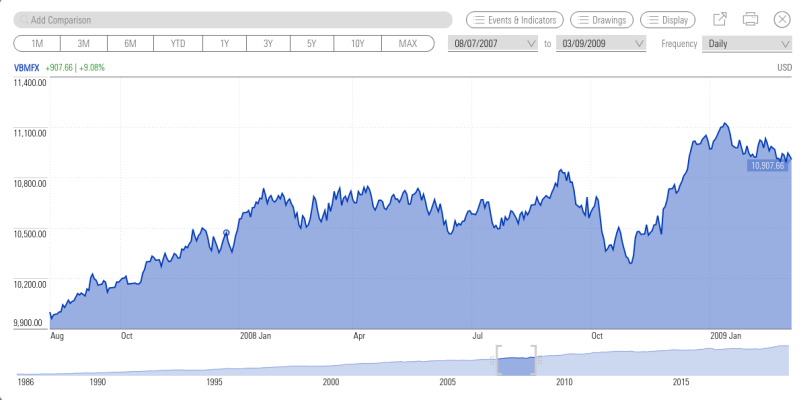

I am figuring on 3% nominal for the next 10 years with no more than 3% inflation, if we make no changes.

Our horizon is 20 years.

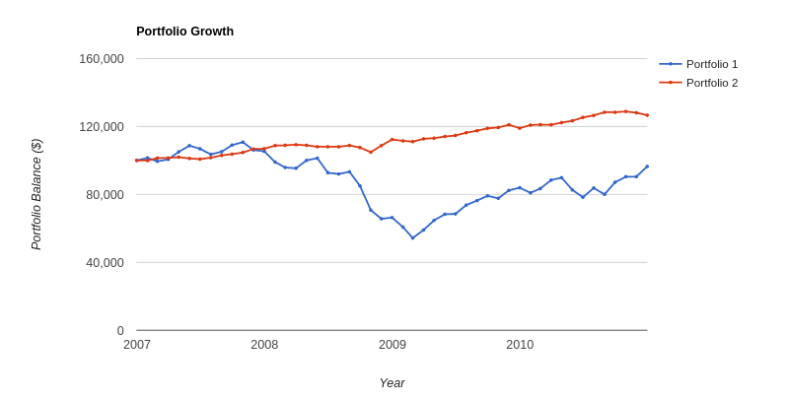

If everything goes to Hell, we will make changes and be OK. We can make radical changes. Most people can't.

Pastafarian here.

Our basic needs and more are covered by SS, but we are drawings down our TIRA and my Roth.

I am figuring on 3% nominal for the next 10 years with no more than 3% inflation, if we make no changes.

Our horizon is 20 years.

If everything goes to Hell, we will make changes and be OK. We can make radical changes. Most people can't.

.

.