Gone4Good

Give me a museum and I'll fill it. (Picasso) Give me a forum ...

- Joined

- Sep 9, 2005

- Messages

- 5,381

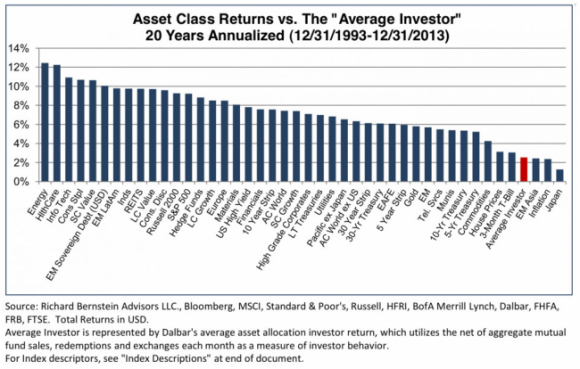

Why does the "average" investor earn just 2%? It is because they are market timers.

I think that's the implication. This is what it says at the bottom of the chart:

“Average investor is represented by Dalbar’s average asset allocation investor return, which utilizes the net of aggregate mutual fund sales, redemptions and exchanges each month as a measure of investor behavior”