ziggy29

Moderator Emeritus

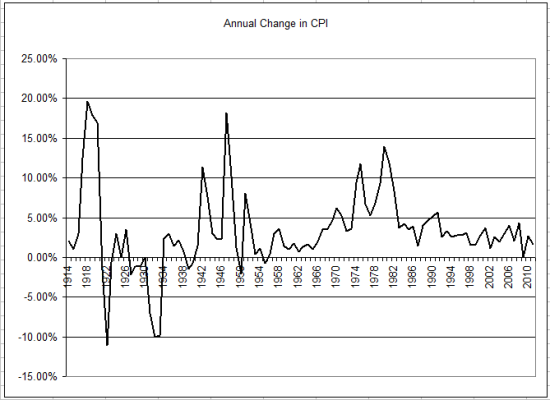

I think part of the problem now is that so much inflation is tied to oil prices -- it affects the cost to produce almost everything -- and every time the economy improves the oil markets spike, which (a) creates more inflationary pressures in the pipeline and (b) threatens to derail the attempt at recovery. IMO, cheap oil circa 2009 did more to revive the economy than government stimulus ever could. And no amount of "policy" will overcome spiking oil prices in a world economy dangerously dependent on it.

So we're in a situation where I think it will be really hard to really break an inflationary tendency in a decent economy because oil market speculators and others who increase industrial demand will see to it that oil prices get really high. It takes very little incremental change in supply or demand to move prices a LOT right now.

I just don't see any sustained improvements in consumer confidence or business climate as long as we have a situation where any economic improvement is met with the bucket of cold water in the energy markets.

So we're in a situation where I think it will be really hard to really break an inflationary tendency in a decent economy because oil market speculators and others who increase industrial demand will see to it that oil prices get really high. It takes very little incremental change in supply or demand to move prices a LOT right now.

I just don't see any sustained improvements in consumer confidence or business climate as long as we have a situation where any economic improvement is met with the bucket of cold water in the energy markets.

Last edited: