Toddtheformeraccountant

Recycles dryer sheets

A very interesting article from Kitces that kind of made me rethink how to factor in taxes to the safe withdrawal rate.

https://www.kitces.com/blog/the-impact-of-taxes-on-the-safe-withdrawal-rate/

I have seen many here advocate simply adding the amount of taxes you will pay (along with your living expenses) into the amount that will need to be "covered" in terms of ongoing costs. I've done the same thing in my planning.

However, what that method fails to consider is that, in the very negative downside scenario, there will actually be very little taxable income and taxes to pay (ie., if you're just drawing down principal). And on the upside scenario, where values are increasing and income is increasing, the fact that you're paying more taxes is irrelevant because you're in "fat city."

So that "add tax expense to the cost" (let's call it the "add taxes" method) overstates the negative. Income taxes only hit if..well...you actually have income to tax. For example, for me, my expected withdrawal rate is 2.75% on the "add taxes" method, 1.7% excluding taxes.

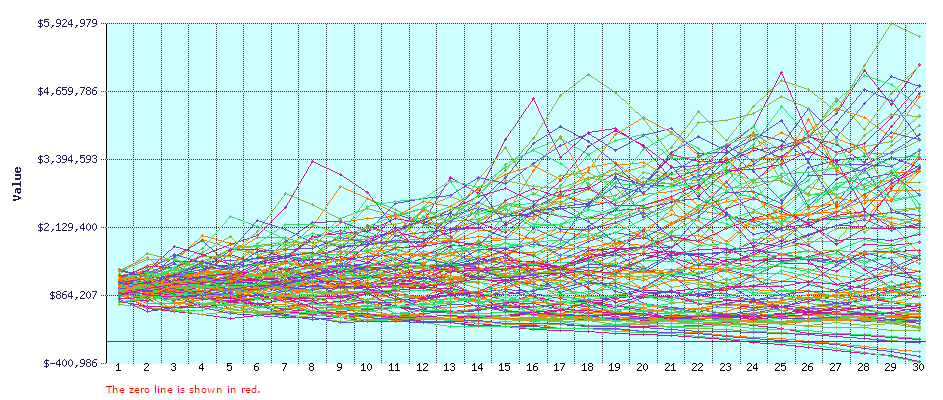

Kitces instead displays here the computations that consider these upside and downside scenarios properly, and you are to use those percentages against an "adjusted" safe withdrawal rate scaling down from the standard 4% (with "no" taxes) to about 3.5% (when you are at top tax rates).

So my "cushion" is actually much higher than it appears with the "add taxes" method. 2.75% "add taxes" actual WR vs. 4% SWR is a 1.25% cushion....but reality is it should be 1.7% actual WR compared to 3.5% max tax rate effected cushion or a 1.8% cushion...55 bps higher cushion. All because, under the "add taxes" method, the downside scenario effectively imputes a tax that will not occur under that scenario. 55 bps more cushion may sound small but we all know that's a HUGE difference.

Wondering what other folks thoughts are, maybe this is a "duh" and here I am thinking I've found the holy grail and the rest of you may be "well no sh** sherlock."

https://www.kitces.com/blog/the-impact-of-taxes-on-the-safe-withdrawal-rate/

I have seen many here advocate simply adding the amount of taxes you will pay (along with your living expenses) into the amount that will need to be "covered" in terms of ongoing costs. I've done the same thing in my planning.

However, what that method fails to consider is that, in the very negative downside scenario, there will actually be very little taxable income and taxes to pay (ie., if you're just drawing down principal). And on the upside scenario, where values are increasing and income is increasing, the fact that you're paying more taxes is irrelevant because you're in "fat city."

So that "add tax expense to the cost" (let's call it the "add taxes" method) overstates the negative. Income taxes only hit if..well...you actually have income to tax. For example, for me, my expected withdrawal rate is 2.75% on the "add taxes" method, 1.7% excluding taxes.

Kitces instead displays here the computations that consider these upside and downside scenarios properly, and you are to use those percentages against an "adjusted" safe withdrawal rate scaling down from the standard 4% (with "no" taxes) to about 3.5% (when you are at top tax rates).

So my "cushion" is actually much higher than it appears with the "add taxes" method. 2.75% "add taxes" actual WR vs. 4% SWR is a 1.25% cushion....but reality is it should be 1.7% actual WR compared to 3.5% max tax rate effected cushion or a 1.8% cushion...55 bps higher cushion. All because, under the "add taxes" method, the downside scenario effectively imputes a tax that will not occur under that scenario. 55 bps more cushion may sound small but we all know that's a HUGE difference.

Wondering what other folks thoughts are, maybe this is a "duh" and here I am thinking I've found the holy grail and the rest of you may be "well no sh** sherlock."