LOL!

Give me a museum and I'll fill it. (Picasso) Give me a forum ...

- Joined

- Jun 25, 2005

- Messages

- 10,252

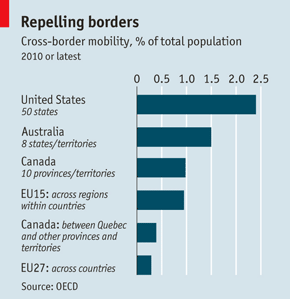

I think it is not uncommon for college-educated folks to move a little bit even though they have a preference for being near family and friends.

But less educated folks really do not just pick and move for jobs as much. They just cannot afford it for the most part.

There was that exodus in the 1980s from Michigan to Texas though.

But less educated folks really do not just pick and move for jobs as much. They just cannot afford it for the most part.

There was that exodus in the 1980s from Michigan to Texas though.