Midpack (et al) ;

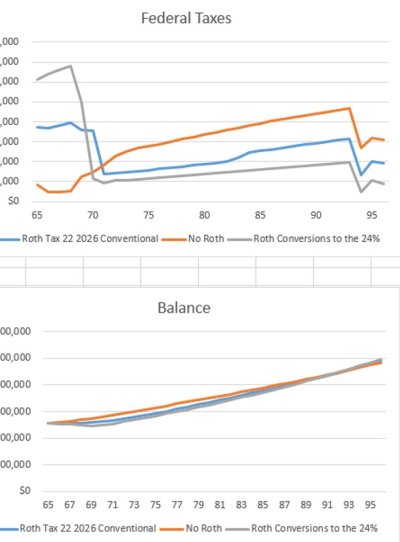

Thanks for the thread! I am new here but read through the entire thing! I am curious to know where your income stream (money that you actually spend) is coming from? I assume if you are like me and my wife we are looking at $4-6K/ month in retirement. We probably have to convert from tIRA to Roth up to the 24% limit over 10 years. I will be retiring in Feb 2020 at 60 yo.

It seems like a real balancing act to try and limit "income" to the 24% over 10 years (before RMDs). Any suggestions? I have some taxable accounts I could draw off of for a couple of years and some cash in the bank.

PS..glad I stumbled across this site. I am trying to keep it simple