marko

Give me a museum and I'll fill it. (Picasso) Give me a forum ...

- Joined

- Mar 16, 2011

- Messages

- 8,462

Right up front: I'm far from a math wiz.

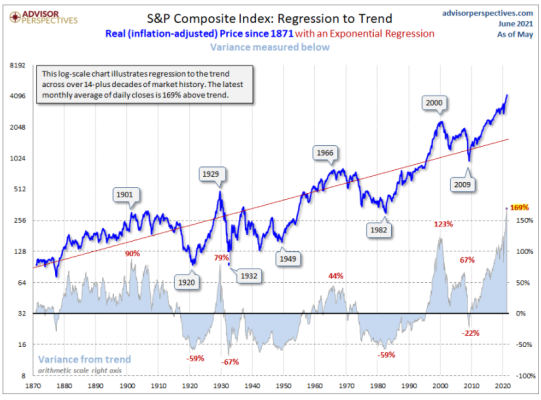

I keep reading about stocks "reverting to mean".

Yes, I'm not such a dope that I don't know what 'mean' means, but I'm wondering how the mean is defined.

It is a 3 year, 5 year, 10 year average? Over time a stock's mean should/could change considering the wild market swings over the past 15 years; I'd assume 2008 and 2020 would figure into a long term average to some extent.

Companies change their positions in the market over time as well (ex: GE), so how is the mean arrived at?

Per usual, I could be entirely in the weeds here so apologies in advance if so.

I keep reading about stocks "reverting to mean".

Yes, I'm not such a dope that I don't know what 'mean' means, but I'm wondering how the mean is defined.

It is a 3 year, 5 year, 10 year average? Over time a stock's mean should/could change considering the wild market swings over the past 15 years; I'd assume 2008 and 2020 would figure into a long term average to some extent.

Companies change their positions in the market over time as well (ex: GE), so how is the mean arrived at?

Per usual, I could be entirely in the weeds here so apologies in advance if so.