56 year old early retiree from San Diego

Hi,

I'm interested in hearing feedback on the analyses shown below (see link to entire article, along with excerpt). As a 56 year old early retiree currently invested 40 stocks / 40% bonds / 20% cash/CDs (to allow breathing room for fluctuations in markets and possible investment in additional rental property), I'm wondering if going even more conservative (to 20 - 30% stock) for the first 5 years is a prudent decision. Thoughts?

Asset Allocation for Early Retirees | Hull Financial Planning

I created a market and inflation simulation to see if this couple could make it to age 95 without running out of money. I used historical market returns for stocks, ranging from an annual loss of 44.2% to an annual gain of 56.8% and a median return of 10.5%, and for corporate bonds, ranging from a minimum annual gain of 2.5% to a maximum annual gain of 15.2% with a median gain of 5.2%, to determine this couple’s returns over time. Each year, the simulation picked a random return for stocks and bonds as well as choosing a random amount inflation, ranging from 10.5% deflation to 18% inflation with a median inflation of 2.8%.

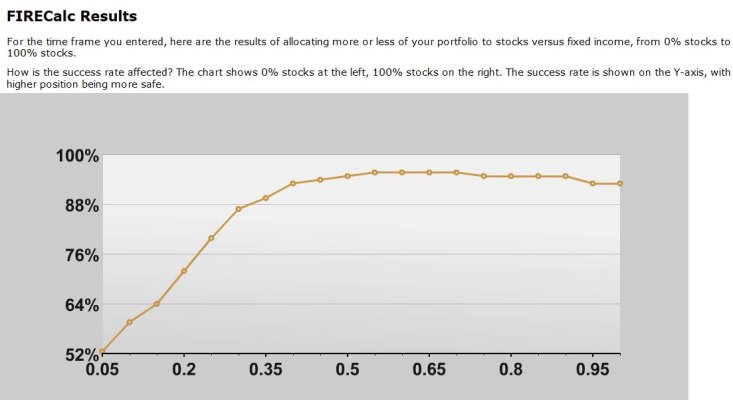

I ran the simulation 10,000 times to see how often our couple had money at age 95.

They had a positive net worth at age 95 89.4% of the time. 50% of the time, they had more than $32.5 million, and 50% of the time, they had less than that amount.

When I construct model scenarios, I usually like to aim for a 90% or higher success rate. This is right on the borderline, but if this couple was a client of mine, I’d give them the go-ahead with a few warning signs to look out for.

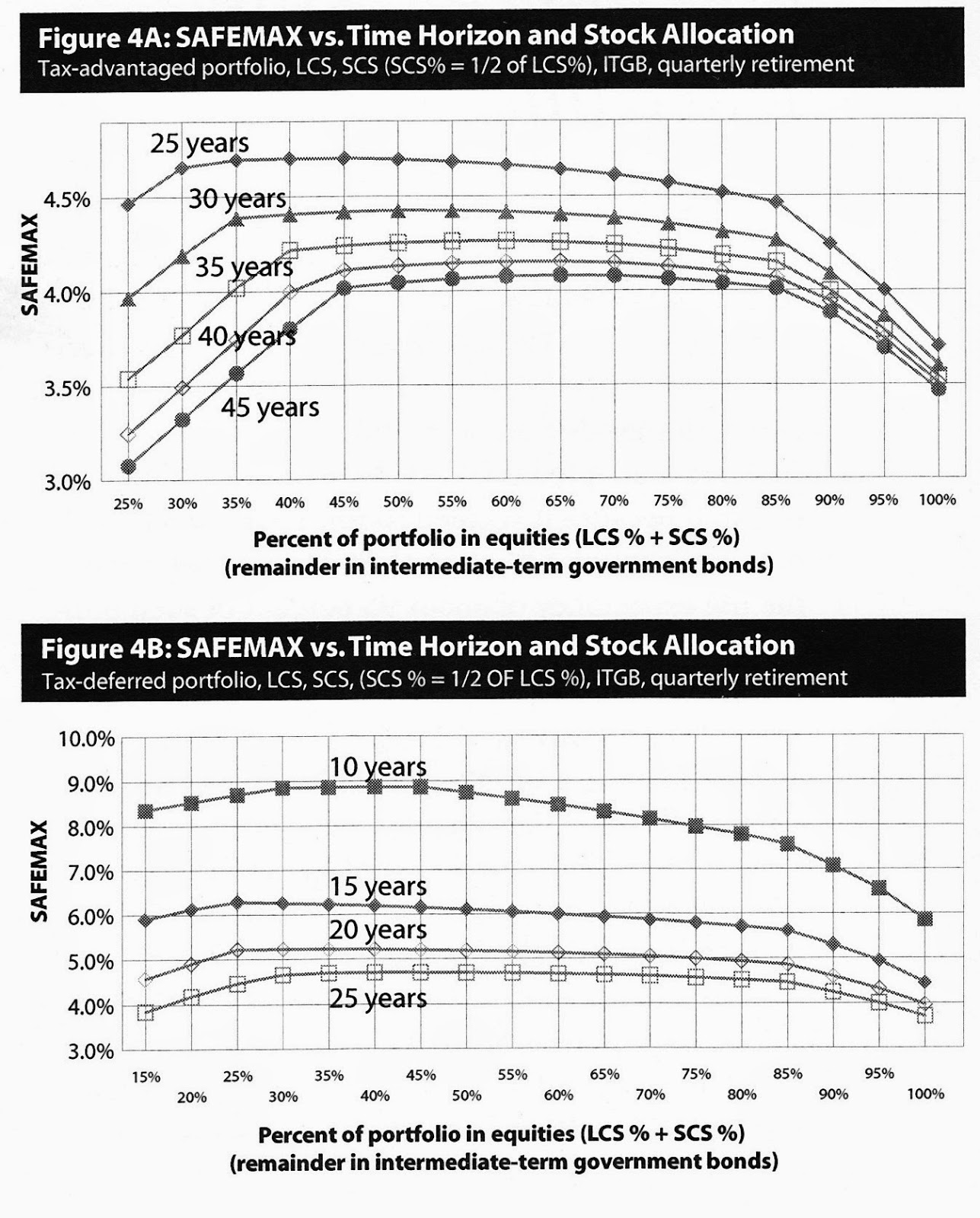

However, recent research by Dr. Wade Pfau, CFA shows that

you’re most vulnerable to poor market performance in the first few years of retirement. His research was limited to 30 years of earning income and 30 years of retirement, but in that research, he showed that returns in the first year of retirement explained more than

14% of the final outcome for those retirees. Since the risk is mainly poor market performance in those first few years of retirement – bad years compounded with withdrawals when the total amount of money that the retirees have is expected to be at its lowest – I decided to tweak the strategy to determine if I could improve on this couple’s outcome.

Instead of using the 110 – age asset allocation strategy that would lead to the couple being invested 70% in stocks the first year of retirement, I had them only 20% invested in stocks and 80% invested in corporate bonds for the first five years of their retirement. The results?

This time, they had money left over 93.4% of the time, and their median net worth was $30.6 million. A shift lower by about $2 million to get well into the safety zone is a tradeoff that I’d be willing to make.

If 5 years is good, then 10 years should be better, right?

Yes and no.

The couple had money left over 94.6% of the time – a much smaller increase in safety. They also had a median net worth of $28.4 million. They paid more for a smaller increase in the cushion.

This makes sense intuitively, as, aside from investing completely in annuities, it’s nearly impossible to gain complete safety when investing in the market. Additionally, the longer that the couple is so heavily invested in bonds, the more likely it is that inflation could catch them.

The counterintuitive approach that Dr. Pfau advocates for the first few years of retirement for people in their sixties seems to hold true for early retirees as well: shift into more conservative investments for a few years and then shift back into more aggressive investing. There’s a balance in asset allocation in retirement

between being too conservative and having your portfolio decimated by inflation and being too aggressive and having unfortunate downturns in the market just as you retire destroy the value of your portfolio. Based on my analysis, portfolio

protection in the first few years of early retirement seems to be a prudent approach in improving the chances of having your money outlast you.

Is this surprising information? What do you think? If you go conservative early in retirement, will you have the fortitude to dial the risk back up in a few years? Let’s talk about it in the comments below!