jimbee

Thinks s/he gets paid by the post

- Joined

- Oct 11, 2010

- Messages

- 1,229

OK, your evidence, please? Statistical studies, academic research, etc. similar to what I had in the OP, not anecdotes.

No evidence presented yet.

OK, your evidence, please? Statistical studies, academic research, etc. similar to what I had in the OP, not anecdotes.

The title is careful to say "near-random." Proof that the market is not perfectly random is as simple as observing that the distribution is biased, which I did in the post. The existence of momentum, also pretty well settled science, also proves that it is not perfectly random. The Andrew Lo book, which I have, also serves.

The point is that not-quite-perfect randomness is proven well enough to explain most of what we as investors see and the decisions we have to make. Inability to time the market is probably the most important. It's the other side of the predicting-the-market coin.

I have deliberately avoided the Efficient Market Hypotheses because it is not necessary to support the assertion and it is hardly a settled matter. (For those interested, here is a 40 minute video that I enjoy and learn from every time I look at it. Two Nobel Prize winners discussing the topic. https://review.chicagobooth.edu/economics/2016/video/are-markets-efficient)

That is not to say that it is impossible for little investors to nibble around the edges of imperfect randomness and maybe get a chunk of cookie from time to time. @NW-Bound has mentioned a few. Occasionally winning a momentum bet, taking advantage of the market's imperfect reaction to earning announcements, and occasionally succeeding in exploiting an overreaction to an event. This is sort of protected territory for the little guy IMO because his tiny money does not move the market. A professional running a significant portfolio must make large enough trades that they will reduce or eliminate his success even if he sees the same little things that the little guy sees. Which he probably does.

But the tricks that a small investor might successfully execute don't, I think, matter for the vast majority of investors on this site because they are not equipped or inclined to do them. For that majority, accepting real world randomness should help them understand why betting on sectors increases risk, why chasing successful managers is doomed, and why the best policy is to completely ignore the talking heads, click-seekers, and hawkers of expensive mutual funds.

Nice. Yes. I guess I never thought of myself as a low pass filter though.Another way to look at it is, there is a lot of noise in the signal, but a low-pass filter shows an increase over time.

There are about 10,000 mutual funds in the US; if we set 10,000 monkeys to flipping coins, after the 8th toss about 40 of them will have flipped ten heads in a row.

I don't understand this part. How could 40 monkeys flip ten heads in a row after only 8 tosses?

It'sjust the math. Start with 10,000 monkeys standing (there are about 10,000 mutual funds), have them flip their coin and sit down if it comes up tails. This leaves about 5000 monkeys standing. Flip again, 2500 standing and so on. You can make a little 8-line spreadsheet and see it all.I don't understand this part. How could 40 monkeys flip ten heads in a row after only 8 tosses?

Still, not a one of those 10K monkeys got 10 heads in 8 flips.

Still, not a one of those 10K monkeys got 10 heads in 8 flips.

But the point is that stock pickers with above-average results do not disprove the near-randomness assertion. Another way fund marketers mask the randomness is with incubated funds: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/i/incubatedfund.asp and by ignoring survivorship bias: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/s/survivorshipbias.asp

I don't have the stats at hand, but I have read that real-world stockpickers that outperform typically do it by only a few percent while the underperformers lose more. This has to be the case at the macro level where decades of evidence show that most stock-pickers underperform...

There's no "settled science" as the thread title proclaims.

See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Random_walk_hypothesis

Economic theory, may be proved in the future.

Nice. Yes. I guess I never thought of myself as a low pass filter though.

Why do you say that?... using the track record of active managers as evidence the market is random is apple and oranges. ...

The title is careful to say "near-random." Proof that the market is not perfectly random is as simple as observing that the distribution is biased, which I did in the post. The existence of momentum, also pretty well settled science, also proves that it is not perfectly random. The Andrew Lo book, which I have, also serves.

The point is that not-quite-perfect randomness is proven well enough to explain most of what we as investors see and the decisions we have to make. Inability to time the market is probably the most important. It's the other side of the predicting-the-market coin.

I have deliberately avoided the Efficient Market Hypotheses because it is not necessary to support the assertion and it is hardly a settled matter. (For those interested, here is a 40 minute video that I enjoy and learn from every time I look at it. Two Nobel Prize winners discussing the topic. https://review.chicagobooth.edu/economics/2016/video/are-markets-efficient)

That is not to say that it is impossible for little investors to nibble around the edges of imperfect randomness and maybe get a chunk of cookie from time to time. @NW-Bound has mentioned a few. Occasionally winning a momentum bet, taking advantage of the market's imperfect reaction to earning announcements, and occasionally succeeding in exploiting an overreaction to an event. This is sort of protected territory for the little guy IMO because his tiny money does not move the market. A professional running a significant portfolio must make large enough trades that they will reduce or eliminate his success even if he sees the same little things that the little guy sees. Which he probably does.

But the tricks that a small investor might successfully execute don't, I think, matter for the vast majority of investors on this site because they are not equipped or inclined to do them. For that majority, accepting real world randomness should help them understand why betting on sectors increases risk, why chasing successful managers is doomed, and why the best policy is to completely ignore the talking heads, click-seekers, and hawkers of expensive mutual funds.

Care to comment on the randomness of the chart before we go off on tangents?Why do you say that?

I have no disagreement with that. The randomness is introduced at the next level up where the pros are getting stirred up by the random and unpredictable things are constantly occurring: a general gets assassinated, earnings reports include surprises, oil producers increase or decrease production, countries' GDP numbers come out, Korea and Japan get into a pi$$ing contest, .... The list goes on and on.Market behavior is not random, but it is driven by the professional money managers, traders and investors and it is foolish for an individual casual investor to believe that they can develop any insight for how financial markets will perform over any particular period of time. The best such investors can hope for is to ride the wave and hope the law of averages works out ok in the long run.

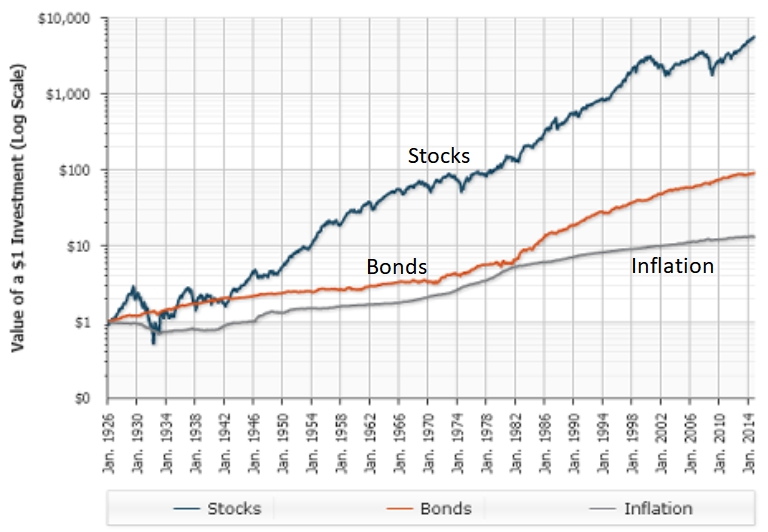

Sure. Your chart pretty much shows graphically what I said in the OP: I say "near-random" because [if] the market were completely random (classical Gaussian distribution) the deviations would be centered on zero and there would be no point in investing because the markets would never change. Actually the distribution is centered a few percent to the right/positive, resulting in what we have seen in a hundred years of market history: a slow, steady trend interrupted frequently by random excursions. That's why buying and holding a diversified portfolio works. The buy and hold investor basically believes in and rides the trend, ignoring the noisy excursions.Care to comment on the randomness of the chart before we go off on tangents?

In 2018 when I was researching for my Adult-Ed investing course I spent some time with a TDAmeritrade branch manager. At that point in time they seemed to be working to become more like a Schwab or a Fido, deemphasizing their hisorical strength as a broker for retail day traders.... Yet, some rare day traders can use that daily randomness to make money. I surely want to watch them in action to see how they can divine the market movement on such short terms.